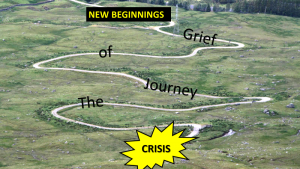

Death is an event; loss of anything significant is an event. It happens and that is it, but the repercussions, known as grief is a process. It is a journey. Usually we think of grief in relation to death but grief can affect you whatever loss you have experienced. Grief is a natural response to loss. It can make other stresses harder to handle and in itself can be a cause of stress.

Coping with grief is about understanding what is happening, working through it and being patient while grief, as a natural process, runs its course. It is a unique journey for you – no one else will experience it in quite the same way as you do. You should not compare your grief with someone else’s. Nevertheless, there are phases that everyone goes through – some are quicker than others and are not always in the same order. In these notes I will mainly relate this to the loss due to death but bear in mind all of this relates to any significant loss.

Because depression and anxiety can be major features of grief, as well as being part of a medical illness, there is the potential to medicalise the journey of grief. Sick leave is taken. Antidepressants and/or sleeping tablets are prescribed. All may have a role on occasion but it is important to be clear that these are only ancillary aids that sometimes, but not in every situation, may be appropriate. They are not treating the underlying cause. Grief is not an illness. It is a natural process. It is a journey that needs to be taken and completed. Grief cannot be ‘treated,’ but the way you cope can be helped so the journey becomes less distressing.

Mourning describes one aspect of grieving where the focus is on the one who has died. Recollections will be about the one who has gone, what they did, what they meant and how they can or should be remembered. This process may be influenced by social conventions or cultural and religious customs and ceremonies. It usually culminates in a funeral service when there is an opportunity for family and friends to gather, recall stories about the departed and have a formal service for the disposal of the body usually by burial or cremation. Mourning is an essential aspect of grieving and requires time and concentration. It should not be hurried especially if you are a ‘chief’ mourner. Your needs ought to be accommodated by family and friends and society. In previous generations there were established customs for mourning such as not mixing in society for a period of some weeks, or even up to a year, wearing black, keeping house curtains closed until the funeral and neighbours doing the same on the funeral day. Some families maintain their own traditions and some ethnic groups have a cultural heritage that designates how mourning should be conducted. Omitting these can add to the emotional suffering of those involved and can be a source of stress even years later. If you have inadvertently missed the mourning rituals, perhaps because of illness or being abroad, you may experience a deep unhappiness that hinders the resolution of your grief. Unresolved grief can also occur if there is no body to mourn over and bury. This might occur, for example, if your loved one died and was buried abroad or has been lost at sea. In these cases, it can be helpful if some form of ceremony is conducted so you can obtain a measure of closure and are enabled to continue your journey of grief.

A similar process of mourning may take place even when the loss has not been by death. For example, when redundancy takes place there may be social pressure from family and friends to find equivalent or better employment as quickly as possible to maintain income and social standing but emotionally this may not be appropriate. If you are redundant you will go through a grieving process so may be depressed. This may come across in interviews as a lack of ambition, drive and competence and result in lack of success in finding alternative employment. That can add to a sense of despair and failure adding to the stress of the redundancy. Better success may well be achieved by taking time out for weeks or even months before looking for new employment. Some may consider accepting ‘stop-gap’ employment as a deliberate policy to allow time both for mourning and to enable unpressurised planning for the next career stage.

The stages of grief

Psychologists recognise that grief has five stages. Describing the process as stages implies that there is a linear progression along this journey. This is only approximately true, for every journey of grief is unique. You may go through the stages in a different order to other members of the family or friends also affected by the loss. Some go through two stages at the same time and others may flip back to a former stage, though if this happens it is usually only a brief return. Bear this in mind as you reflect on your own journey of grief.

1 Denial

Shock, numbness, confusion and conflicting feelings are common when a loss occurs especially if it is unexpected. You may ‘freeze,’ be unable to do anything, think straight or ask questions about the loss. You may need someone to take over your role but because of being frozen are unable to ask for or authorise this. This is an emotional reaction, it is not rational. It is as if not doing anything will mean it will all go away and life as you knew it will be restored. People may not realise what is happening to you so may become angry with your lack of apparent interest and unwillingness to discuss the situation and make decisions. They may then make inappropriate decisions that you, and they, will later regret.

Shock, numbness, confusion and conflicting feelings are common when a loss occurs especially if it is unexpected. You may ‘freeze,’ be unable to do anything, think straight or ask questions about the loss. You may need someone to take over your role but because of being frozen are unable to ask for or authorise this. This is an emotional reaction, it is not rational. It is as if not doing anything will mean it will all go away and life as you knew it will be restored. People may not realise what is happening to you so may become angry with your lack of apparent interest and unwillingness to discuss the situation and make decisions. They may then make inappropriate decisions that you, and they, will later regret.

Sometimes you may appear to be in control. You ask the right questions and make the right decisions but inside you may feel emotionally numb. It may feel as if you are in a bad dream so if you hang on you will wake up and life will go back to normal. So you do not express any emotion. There are no tears and you sleep well. It is like being on auto-pilot.

As well as or alternatively, the withdrawal may be physical instead of emotional. You may not want to meet people. You may stay at home rather than meet friends. You might even take to your bed and stay there for days on end.

All this is about denial – being unable to accept what has happened and failing to face the implications the loss has brought. There is an English idiom about burying your head in the sand that may be used but it does not truly express what is happening. This idiom is based on the myth that ostriches bury their head in the desert sand when faced by a predator thinking that if they cannot see the danger they will not be seen. The denial in grief, though is not intentional. It is a normal stage in the journey of grief.

Sometimes the denial stage recurs when you appear to be well on the way to recovery. You may unexpectedly meet someone who asks how you are or expresses sympathy for your loss – and you tell them you are fine or ask what they are talking about. It can be embarrassing for both parties! You are not losing your mind. This is a normal reaction as, although you are recovering, part of the recovery at this stage is to lock away the unhappy memories so you can cope with other aspects of your life. You will deal with those memories when you are ready but at this stage you unconsciously find it better to ignore them – and your friend happens to have caught up with you during one of those lock-out phases. This illustrates how the denial stage is not an active rejection of the truth but instead is an emotional protective mechanism. It is a normal physiological response.

Six months after the unexpected death of her husband Felicity would sometimes buy food for two and even lay the table for two. She wondered if she was going out of her mind but her doctor reassured her and explained that this was a normal aspect of the denial stage in the journey of grief. He explained also that old habits can be difficult to change. He suggested that she should think of creative ways to use the extra food so she was prepared for when it happened again. She could, for example, plate up the food and then freeze it for a ready-made meal to use later or sometimes arrange for a friend to visit for a meal. He reassured her this was a normal phase of grief and gradually she would learn new habits.

Denial is not bad in itself. It is a normal part of the grieving process. It gives time to absorb unwelcome news and acts as an inbuilt form of self-protection. It can, though lead to difficulties and inevitable stress if not recognised or handled correctly. This is when you need family and friends who can gather round, support and even take control for a while – but more of that later. In time the shock, numbness and confusion begin to wear off and emotions start to be expressed.

2 Anger

You will have tears of sadness and loss and fears about the future but anger is the predominant emotion in the next stage of bereavement. Your loss has now been accepted but not with resignation. The shock and confusion give way to pain, emotional pain. Questions arise apparently quite spontaneously:

You will have tears of sadness and loss and fears about the future but anger is the predominant emotion in the next stage of bereavement. Your loss has now been accepted but not with resignation. The shock and confusion give way to pain, emotional pain. Questions arise apparently quite spontaneously:

‘Why has this happened?’

‘What went wrong to cause this tragedy?’

‘Who made a mistake?’

‘Someone is to blame, who is it? They must pay for their mistakes.’

So your anger may be expressed in complaints of unfairness or accusations of failure or culpability – without any request for explanations. And if you do request any, you may respond by interrupting or dismissing what is said. There may be little premeditation of these complaints so they may be addressed, almost randomly, to the one bringing the message about the loss or to those who have devotedly cared for a loved one who has died. This can then lead to family rifts and fall-outs with friends or professional carers. It depends on the exact circumstances of course, as sadly the care of a terminally ill patient may not be the best, but this reaction can be entirely due to the emotional stress of bereavement.

God is often targeted and it may be in the form of questions such as:

‘Why me?’

‘Why my loved one?’

‘What have I done to deserve this?’

‘Where is God when he is needed?’

Sometimes you may express your anger by blaming yourself and perversely, the one who has died may be blamed:

‘She only did this to spite me.’

Anger with yourself may be expressed as regret or guilt about things you did or did not say or do. After a loss such as death or divorce, you may feel guilty for not doing something to prevent it, even if there was nothing that could have been done.

This stage, once again, is a normal part of the journey of grief. Such anger needs to be expressed, it should not be suppressed, for only then can it be dissipated. Sadly, sometimes situations do go wrong and there may be a genuine reason for the suspicions underlying the anger but if you are the one who is grieving you are not the best person to assess the situation. This should be done by someone who is not emotionally involved and has the knowledge and experience to make an unbiased assessment. Much more commonly there is a need to rescind accusations, apologise and put right misleading information.

3 Bargaining

If the loss occurs unexpectedly this stage may not feature at all. It is much more likely to occur when a significant loss has not yet happened but is inevitable. This could be due to the loss of a close relative or friend due to an illness such as cancer. It could relate to the anticipation of the cessation of employment due to retirement, redundancy or even in the natural stages of career progression. It is particularly a feature of the grief experienced by those who are anticipating their own death. In these situations the grief reaction may start many months before the loss actually takes place.

If the loss occurs unexpectedly this stage may not feature at all. It is much more likely to occur when a significant loss has not yet happened but is inevitable. This could be due to the loss of a close relative or friend due to an illness such as cancer. It could relate to the anticipation of the cessation of employment due to retirement, redundancy or even in the natural stages of career progression. It is particularly a feature of the grief experienced by those who are anticipating their own death. In these situations the grief reaction may start many months before the loss actually takes place.

This stage takes the form of bargaining with those in authority. However, the bargaining may be only in day dreams and nightly ruminations. The employer, person who is dying or others may know nothing about your thoughts. Sometimes it is God to whom the bargaining is addressed.

This stage is characterised by statements such as:

‘Make this not happen, and I will …’

These may be made to God or to doctors or lawyers who have been involved. Other phrases used include:

‘If only…,’

‘I wish…,’

‘Why …’

4 Despair

Once the shock has passed, the actuality of events has been accepted and protests expressed in anger and hurt have failed to satisfy, the reality will strike home to you that life will continue in spite of the loss. Sometimes that is unbearable even to the extent of contemplating suicide. As a passing thought, this is common but tragically some go further and take action though they are rarely the ones who have put their thoughts into words. Suicide associated with grieving usually comes as a shocking surprise to family and friends and initiates a fresh expression of their own grief.

Once the shock has passed, the actuality of events has been accepted and protests expressed in anger and hurt have failed to satisfy, the reality will strike home to you that life will continue in spite of the loss. Sometimes that is unbearable even to the extent of contemplating suicide. As a passing thought, this is common but tragically some go further and take action though they are rarely the ones who have put their thoughts into words. Suicide associated with grieving usually comes as a shocking surprise to family and friends and initiates a fresh expression of their own grief.

Inevitably, the loss can cause a sense of loneliness and hopelessness. It is all too easy to sit doing nothing. It can be too much trouble to prepare meals and the desire for food may dwindle. You may not think about going out, changing your clothes, bathing or even going to bed. Your energy levels are reduced so the tendency to self-neglect is exacerbated. Fear, anxiousness, feeling insecure and having panic attacks may trouble you. Physical symptoms may occur. These include fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, weight loss or weight gain, aches and pains and insomnia. There can be a sense of being let down by doctors, employers, a loved one, the government, society etc – whoever have had some sort of role in the loss. The question then arises:

‘Who then can I trust?’

Nothing may be said but you may begin to doubt even trusted family members and close friends. You may lose confidence in the future so plans and expectations become pointless. Everything is changed. The world will never be the same again. And God too may be rejected:

‘How can I trust in a God who let me down like that?’

‘How can there be a God of love?’

‘That proves there is no such thing as God.’

Such statements may be made even if you had until then, counted yourself as a committed believer. Such comments, you see, reflect your reaction to loss and are not usually due to a religious deconversion. If you have expressed such thoughts to others, you may later be embarrassed. That is not necessary, though, as they are a reflection of grief and are not usually due to a true loss of trust or of unbelief. Such symptoms of grief are a normal aspect of life. Friends and family need to accept them as such so they should not rebuke or criticise you if you express your grief in this way. Please forgive them. They have probably not been taught that such statements are a normal aspect of grieving. Also, they may well be grieving too and their rebuke may be addressed to themselves as much as to you.

Some people find themselves wondering:

‘Who am I without my loved one?’

This is especially likely if you and your loved one were close for many years. You may have forgotten what you were like before your partner came into your life and your habits of life became entwined with those of your partner. This happens because we all tend to define ourselves by the roles we play in close relationships. We think of ourselves as a husband or wife, brother or sister, child, friend, lover, mentor, caregiver and more. When bereaved, you will lose one or more of these important roles so that raises questions:

‘Who am I?’

‘What do I mean (to other people)?’

And if your ruminations do not lead to a satisfactory conclusion you may wonder to yourself:

‘What is the point of living?’

This confusion and despair will take time to resolve and will only happen as you start again interacting with people. Though you may take up previous roles it is not uncommon to redefine yourself as you make new relationships and discover new roles. Healing from a bereavement can become a new adventure in living – and that introduces the final stage of the grieving process.

5 Integration /New Beginnings

Eventually, you will start to think about the future, will think about making plans and will start to laugh again. Some apparent acceptance may happen quite early as, for example, a funeral requires planning and there may be some necessary decisions to be made about housing or care of children. But that acceptance is forced because of circumstances. It does not reflect an inner emotional acceptance. Sometimes there is no escape so some decisions have to be made but caution is necessary. It is unwise to make any long-term plans in the immediate time after a significant loss as the emotional input is likely to overwhelm any rational assessment about the benefits and drawbacks of the various options that need to be considered.

Eventually, you will start to think about the future, will think about making plans and will start to laugh again. Some apparent acceptance may happen quite early as, for example, a funeral requires planning and there may be some necessary decisions to be made about housing or care of children. But that acceptance is forced because of circumstances. It does not reflect an inner emotional acceptance. Sometimes there is no escape so some decisions have to be made but caution is necessary. It is unwise to make any long-term plans in the immediate time after a significant loss as the emotional input is likely to overwhelm any rational assessment about the benefits and drawbacks of the various options that need to be considered.

At first, recollections of a loved one will have been about the sad aspects of your loss and their suffering but gradually memories of happy times will come to the fore. Tears will be accompanied by smiles and laughter and gradually the tears will lessen and the indicators of happiness will increase. Gradually you will come to terms with the sense of guilt about even the suggestion of enjoying life.

It may be impossible at first even to think of disposing of clothes and possessions but as time progresses you may be able to look through wardrobes and drawers planning to sort them out – but are waylaid by memories, both happy and sad. The task can take ages – but there is no problem about that for it all helps the healing process. Kindly meant offers from family or friends to:

‘sort this out for you, to save you being upset,’

should be rejected or accepted for only a limited role as your assistant.

You never ‘get over’ a bereavement. Life cannot go back to the way it was. You are changed irrevocably. But gradually the dark shadows of your loss become part of you – this is at the heart of what happens in the journey of grief. You adapt to a new role in life so now, for example, being a widow is the real you just as much as your former role as a wife was the real you. This stage is usually referred to as ‘Acceptance’ but that is only part of what happens and it seems to emphasise the loss as being an external event. A better term is integration, especially for a major loss. The changes are not as much in your circumstances though they may be significant enough. You, yourself, are changed. You will never be the same again. The changes may be more than can be expected from the incorporation of memories and life’s experiences. It affects your role in life, the purposes and plans you have for your life and your attitudes and values. It is a time of new beginnings. This process of integration may continue for many years so your life may develop into new fields and new experiences.

Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Despair, Integration

These five stages are a normal reaction to loss. For real healing it is necessary to face your grief and actively deal with it. Grieving is a lonely process and you may try to ‘protect’ your family and friends by putting on a brave face. But they too will be grieving. It will not be in the same way and they may well go through the stages of this journey in a different order and at a different pace. Showing your true feelings can help both them and yourself – but more of that when we reflect on how to deal with grief.

Afterthought

Crying may occur at any stage, it does not mean you are weak. It is natural and seems to help in the healing process. In the initial denial stage it is associated with the shock of loss, in the second anger stage it can be a means of releasing anger and frustration at the unfairness and cruelty of life. In the despair stage it is associated with loneliness, despondency and self-pity. It features also in the acceptance stage when weeping can be closely associated with laughter because of the mixed emotions involved. You are recovering and it is such a release to be able to laugh again but then comes guilt as your loved one is no longer present to share in the laughter so tears can be mixed in with the laughter.

It is all part of the healing process. It seems you cannot cry enough but you can cry too little.

Endnote

Knowledge of the process of grief is based on the work of Dr Elisabeth Kubler-Ross and particularly her book, On Death and Dying, that was first published in 1969.